Heat in the city: Hotter than the thermometer reveals

Urban heat islands (UHI) describe the phenomenon whereby urban areas are significantly warmer than the surrounding countryside. This poses an additional challenge in times of rising global temperatures (Schäfer et al., 2025). When the thermometer shows high readings in cities such as Frankfurt or other densely built-up cities in summer, the actual stress on the urban population is often significantly greater than in the surrounding rural areas. Conventional temperature measurements do not adequately reflect the extent of urban heat stress.

Air temperature alone is not the only factor that determines thermal comfort, i.e., people's subjective perception of heat. Other meteorological factors such as solar radiation, wind, and humidity also play a decisive role. Who isn't familiar with the refreshing cool breeze in the shade? In addition, there are individual factors such as clothing and activity level, which are taken into account in physiological heat balance models. All these influences can be summarized in so-called thermal comfort indices. There are a number of these, which weight the individual influencing factors differently. A comparatively simple index is the Humidex, which combines only air temperature and humidity.

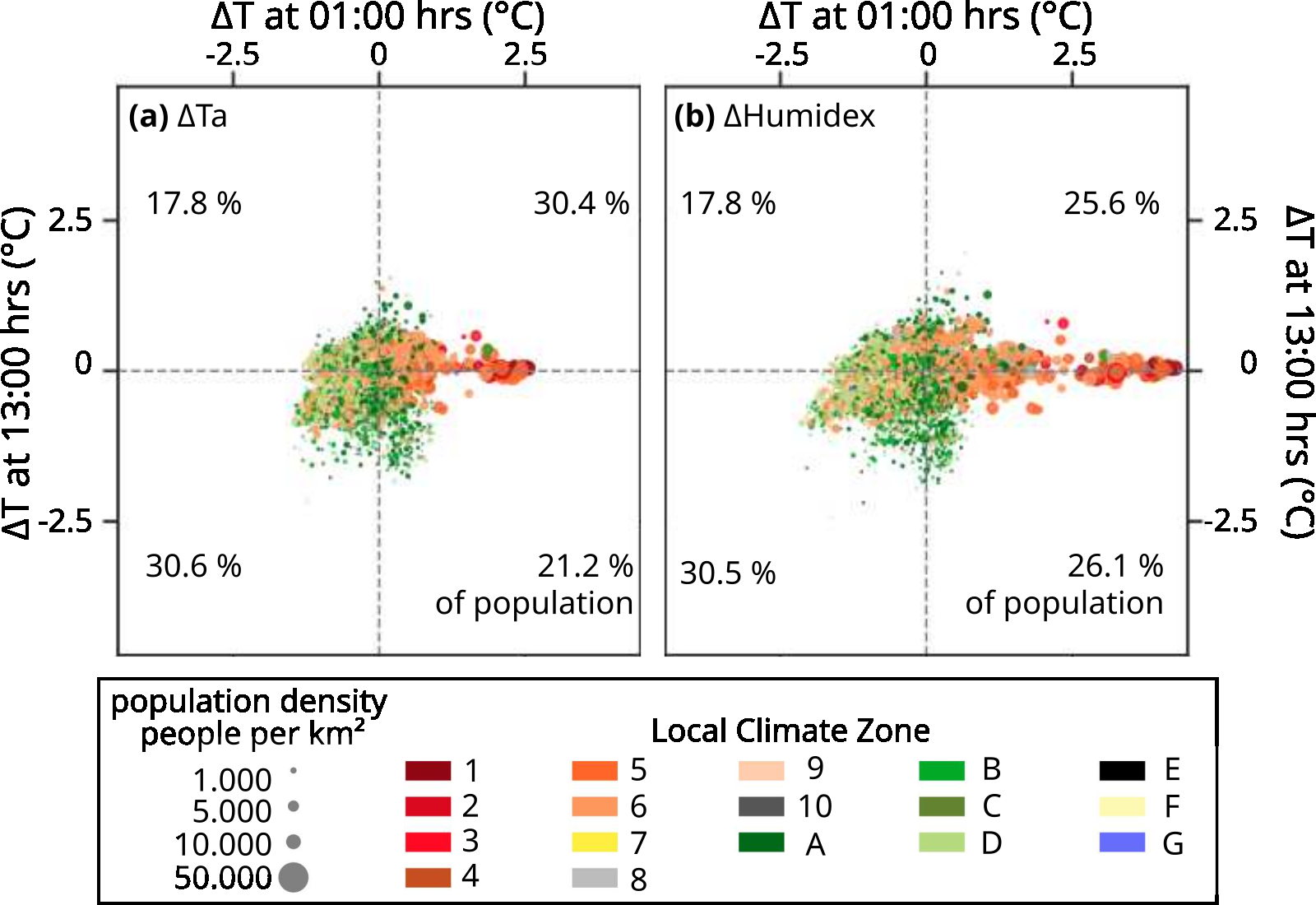

The study by Krikau and Benz (2025) compares various heat metrics, including air temperature, land surface temperature (LST), and the so-called Humidex, which also takes humidity into account. Data with a resolution of 1 km from 2011 to 2020 was used for the state of Hesse. While the pure air temperature at night in the study area of Hesse shows an urban heat island effect (Figure 1) of a maximum of 2.9 °C compared to the surrounding area, the difference in the humidex reaches up to 4.3 °C. This means that the heat in densely built-up areas feels much more intense than the thermometer would suggest. Residents in compact urban neighborhoods (local climate zones 1–3) are particularly affected. Here, it hardly cools down at night, which leads to a prolonged cooling deficit. Around one-third of Hesse's population lives in areas that are significantly hotter than the surrounding rural areas, both during the day and at night. Frankfurt am Main was identified as the district with the highest heat stress.

One point of criticism concerns the use of satellite data. Surface temperatures from space are often used as a substitute for missing weather stations. However, the study highlights limitations: while satellite data is very well suited for identifying local hotspots on extremely hot days, it is less suitable for mapping the duration and intensity of entire heat waves. This means that a red spot on the satellite map shows us where the asphalt is glowing, but says little about how long the stagnant heat will remain in the air.In order to realistically assess the health risks for the urban population, it is not enough to look only at air temperature values/land surface temperature. Those who rely solely on these overlook a large part of the risk, especially on muggy summer nights.

Krikau, S., Benz, S. (2025): Temporal and spatial patterns of heat extremes in Hesse, Germany. Environ. Res. Commun., 7, 051001, https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/adce59.

Schäfer, A.M., Ludwig, P., Krikau, S., Benz, S.A., Mühr, B., Mohr, S., Kunz, M., 2025. The evolution of heat exposure in changing societies and a changing climate from 1960 to 2100. Front. Clim., 7, 1491695, https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2025.1491695.

Associated institute at KIT: Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (IPF)

Autoren: Svea Krikau, Susanne Benz (February 2026)